Inside the Artificial Universe That Creates Itself

A team of programmers has built a self-generating cosmos, and even they don’t know what’s hiding in its vast reaches.

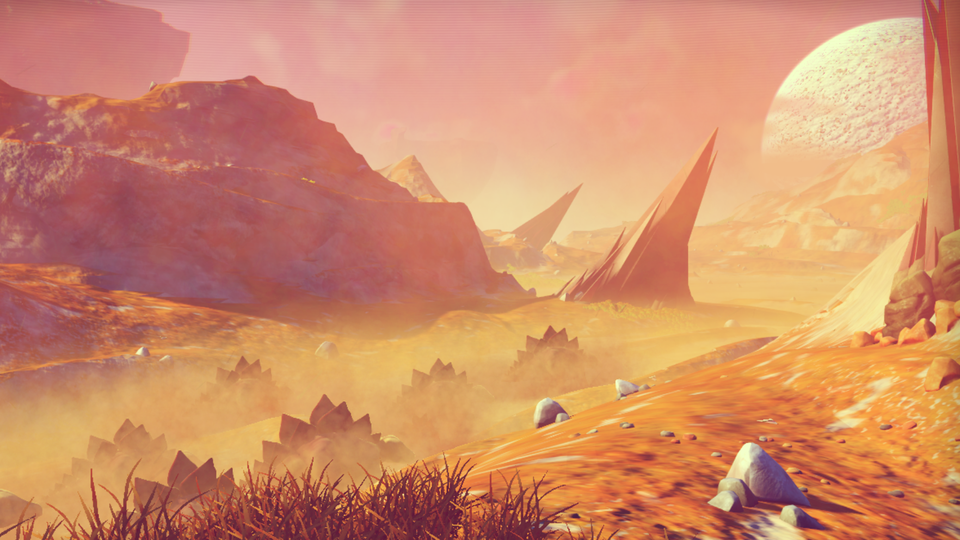

Every particle in the universe is accounted for. The precise shape and position of every blade of grass on every planet has been calculated. Every snowflake and every raindrop has been numbered. On the screen before us, mountains rise sharply and erode into gently rolling hills, before finally subsiding into desert. Millions of years pass in an instant.

Here, in a dim room half an hour south of London, a tribe of programmers sit bowed at their computers, creating a vast digital cosmos. Or rather, through the science of procedural generation, they are making a program that allows a universe to create itself.

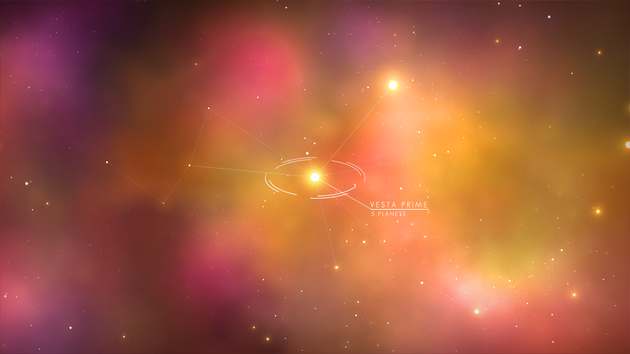

The ambitious project will be released as a video game this June under the title No Man’s Sky. In the game, randomly-placed astronauts isolated from one another by millions of lightyears must find their own existential purpose as they traverse a galaxy of 18,446,744,073,709,551,616 unique planets.

“The physics of every other game—it’s faked,” the chief architect Sean Murray explained. “When you’re on a planet, you’re surrounded by a skybox—a cube that someone has painted stars or clouds onto. If there is a day to night cycle, it happens because they are slowly transitioning between a series of different boxes.” The skybox is also a barrier beyond which the player can never pass. The stars are merely points of light. In No Man’s Sky however, every star is a place that you can go. The universe is infinite. The edges extend out into a lifeless abyss that you can plunge into forever.

“With us,” Murray continued, “when you're on a planet, you can see as far as the curvature of that planet. If you walked for years, you could walk all the way around it, arriving back exactly where you started. Our day to night cycle is happening because the planet is rotating on its axis as it spins around the sun. There is real physics to that. We have people that will fly down from a space station onto a planet and when they fly back up, the station isn't there anymore; the planet has rotated. People have filed that as a bug.”

On the monitor before us, cryptic fragments of source code flash by. While earthly physicists still struggle to find a unified mathematical framework for all phenomena—the No Man’s Sky equivalent already exists. Before us are the laws of nature for an entire cosmos in 600,000 lines.

The universe begins with a single input, an arbitrary numerical seed—the phone number of one of the programmers. That number is mathematically mutated into more seeds by a cascading series of algorithms—a computerized pseudo-randomness generator. The seeds will determine the characteristics of each game element. Machines, of course, are incapable of true randomness, so the numbers produced appear random only because the processes that create them are too complex for the human mind to comprehend.

Physicists still debate whether our own universe is deterministic or random. While some scientists believe that quantum mechanics almost certainly involves indeterminacy, Albert Einstein famously favored the opposing position, saying, “God does not play dice.” No Man’s Sky does not play dice either. Once the first seed number is entered into the void within the program, the universe is unalterably established—every star, planet, and organism. The past, present, and future are fixed indelibly, with change to the system only possible from a force outside the system itself—in this case, the player.

In one sense, because of the game’s procedural design, the entire universe exists at the moment of its creation. In another sense, because the game only renders a player’s immediate surroundings, nothing exists unless there is a human there to witness it.

“Whatever is around you,” Murray mused, “it actually doesn't matter whether it exists or not, because even the things you don’t see are still going about their business. Creatures on a distant planet that nobody has ever visited are drinking from a watering hole or falling asleep because they’re following a formula that determines where they go and what they do; we just don’t run the formula for a place until we get there.”

The creatures are generated through the procedural distortion of archetypes, and each given their own unique behavioral profiles. “There is a list of objects that animals are aware of,” Artificial Intelligence programmer Charlie Tangora explained. “Certain animals have an affinity for some objects over others which is part of giving them personality and individual style. They have friends and best friends too. It's just a label on a bit of code—but another creature of the same type nearby is potentially their friend. They ask their friends telepathically where they’re going so they can coordinate.”

While the basic behaviors themselves are simple, the interactions can be impressively complex. Artistic director Grant Duncan recalled roaming an alien planet once shooting at birds out of boredom. “I hit one and it fell into the ocean,” he recalled. “It was floating there on the waves when suddenly, a shark came up and ate it. The first time it happened, it totally blew me away.”

The team programmed some of the physics for aesthetic reasons. For instance, Duncan insisted on permitting moons to orbit closer to their planets than Newtonian physics would allow. When he desired the possibility of green skies, the team had to redesign the periodic table to create atmospheric particles that would diffract light at just the right wavelength.

“Because it’s a simulation,” Murray stated. “there’s so much you can do. You can break the speed of light—no problem. Speed is just a number. Gravity and its effects are just numbers. It’s our universe, so we get to be Gods in a sense.”

Even Gods though, have their limitations. The game’s interconnectivity means that every action has a consequence. Minor adjustments to the source code can cause mountains to unexpectedly turn into lakes, species to mutate, or objects to lose the property of collision and plummet to the center of a planet. “Something as simple as altering the color of a creature,” Murray noted, “can cause the water level to rise.”

As in nature itself, the same formulas emerge again and again—often in disparate places. Particularly prolific throughout No Man’s Sky (and nature) is the use of fractal geometry—repeating patterns that manifest similarly at every level of magnification. “If you look at a leaf very closely,” Murray illustrated, “there is a main stock running through the center with little tributaries radiating out. Farther away, you’ll see a similar pattern in the branches of the trees. You’ll see it if you look at the landscape, as streams feed into larger rivers. And, farther still—there are similar patterns in a galaxy.”

“When I go out in nature, I don’t even see terrain anymore,” the programmer laughed. “All I see are mathematical functions and graphs. I’ll pick up a stone and begin thinking about the shape of it. What formula could have given you that?”

I mentioned to Murray that I am doing a project collecting dreams from around the world, and asked about his. The programmer reported recurring scenes in which the real world appeared to be just a computer program. That possibility is being seriously considered by many scientists, including a team of physicists from the University of Bonn who recently published evidence in support of it. “Elon Musk questioned me about that,” Murray recalled. “He asked, ‘What are the chances that we’re living in a simulation?’”

The programmer considered the thought before offering a hedge. “My answer,” he said, “was basically that, even if it is a simulation, it’s a good simulation, so we shouldn’t question it. I’m working on my dream game, for instance. I’m more happy than I am sad. Whoever is running the simulation must be smarter than I am, and since they’ve created a nice one, then presumably they are benevolent and want good things for me.”

I rang up Nick Bostrom, Director of the Future of Humanity Institute at the nearby University of Oxford. Bostrom is a longtime proponent of the idea that it’s possible we are living in a simulation. “If the simulation hypothesis is true,” I asked him, “what implications would that have for our existence?”

“One might be the idea of an afterlife,” he said. “From a naturalistic understanding, when we die we basically rot. But if we are in a simulation, if you stop the program, you can restart it again. You can take data created by one program and enter it into another without violating any laws of nature.”

“If this world is a simulation,” I asked, “What does that say about our creators?”

“There might be different motives,” Bostrom acknowledged. “In many ways it has parallels with reconciling evil in the world with an omnipotent and benevolent God. You could say that we are not created by someone who wanted the best for the world, or you could say that all of this suffering is illusory, or you could try to concoct some explanation for why it's actually necessary. Either way, there’s an intellectual challenge there.”

“As a creator yourself,” I asked Murray back at No Man’s Sky headquarters, “How benevolent are you?”

“Well, we don't have blood in our universe. That’s pretty nice. We don’t have cities full of urban problems. We have nice beautiful landscapes more often than not.”

In No Man’s Sky, there is also no sickness, no excrement, and no birth. There is death, but always with the assurance of reincarnation. “When you die, you regenerate in the same location,” Murray explained, “but you do lose a great deal of things. We wanted the loss to be meaningful—for you to know that if you make a decision, it has significance.”

The poignancy of death extends to other creatures as well. “The nature of video games is conflict,” Murray insisted. “It’s an interesting reflection of where we've gotten to. With our game though, you give someone a controller, they land on a planet, they see an alien creature, and if it’s their first time playing, they will probably shoot it even though they have just gone through a journey to get there. What I really like though, is that nine times out of ten, people suddenly feel bad that they’ve done it. You don’t get points for killing. There are no gold coins. You chose to do that.”

The player has no alter ego to hide behind either. “In most games, you begin by choosing a character,” Murray described. “Often you’ll be cast as an unlikable character with a dozen catchphrases. You’ll have a nickname like Irish or Tex. You’re made to decide at the beginning who you are, but that might be before you decide how you really want to play. We want to let people have their imagination. They can be whoever they want to be. They might be an alien if that’s what they want to believe. I quite like that.”

In a universe designed without mirrors, as this one is, the only way that you could ever view yourself would be to ask another player to look at you and describe what they see. Considering the inconceivable vastness of this cosmos however, for two humans to ever chance upon one another would be an almost impossible event—one capable of evoking real awe.

For the No Man’s Sky team, that feeling of awe is exactly the point. In the words of programmer Hazel McKendrick, “You’re not the God of this universe. You're not all powerful. You can’t build a gun so big that you're unstoppable. You should be small and a little bit scared, I think, all the time.”

Murray traces this feeling of sublime obliteration to his childhood deep in the Australian outback. “My parents managed this big ranch of one and a quarter million acres. It had a gold mine. It had seven airstrips. You don’t get there by road—you have to fly in. We were very much on our own, and we went out every morning to check that the machines that were keeping us alive were still working. It was the closest thing to the surface of Mars. We were alone for hundreds and hundreds of miles. There was just this incredible feeling—knowing that you’re this little dot in this massive landscape.”

“The very first thing we talked about when we were planning this game was emotion,” Murray continued. “That emotion of landing on a planet and knowing that no one else has ever been there before. There is a very deep human quality of needing to explore. When other games have exploration, everything has already been built by someone. There is a vocabulary. Certain doors will open and certain doors won’t, and when the door opens, it probably has a little secret inside—a secret shared by thousands of other players that have been there before.”

Through the use of procedural generation, No Man’s Sky ensures that each planet will be a surprise, even to the programmers. Every creature, AI-guided alien spacecraft, or landscape is a pseudo-random product of the computer program itself. The universe is essentially as unknown to the people who made it as it is to the people who play in it—and ultimately, it is destined to remain that way.

“People will stop playing long before even .1 percent of everything has been discovered,” Murray reflected. “That’s just how games are. I would be foolish to think anything else. It’s a sad thought though. When we fly through the galactic map, we see all the stars, each of which will have planets around them, and life, and ecology—and the vast, vast, vast majority will never be visited. At some point the servers will be shut down. It will all be turned off, and it will be us who pull the plug.”